Remembering the "Black City Hall": The Butler Street YMCA

by Maya Henry African American Programs Graduate Research Assistant, Georgia State University. Originally published via the Reflections newsletter of the Historic Preservation Department of GA.

My twenty-two year long educational career began at my local YMCA in New Jersey. The YMCA or the Young Men's Christian Association is a worldwide non-profit movement for projects and services directed to all ages based on principles around strengthening the mind, body and spirit. As a product of the pre-k program at the YMCA, its health facilities and summer camp, I intimately know the positive impacts the YMCA has on children and families. I spent summers and afterschool sessions swimming, visiting museums like the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia PA, and playing soccer. Most known for recreational activities such as athletic teams, fitness classes for various age groups or perhaps its religious origins, the YMCA also had a political history. I discovered Atlanta’s Historic Sweet Auburn District had a Black founded and operated YMCA to serve its community from 1894 – 2012 called the Butler Street YMCA. There were African American YMCAs?

I also learned that only three of these Black YMCAs are still in operation today: Dearborn YMCA, Mobile, Alabama; Dryades YMCA, New Orleans, Louisiana; and West Broad Street YMCA, Savannah, Georgia. Four other Black YMCAs closed or combined with other YMCAs in the area during the 21st century including the Butler Street YMCA, Cannon Street YMCA, Charleston, South Carolina, Garner Road YMCA, Raleigh, North Carolina, and William A. Hunton Family YMCA, Norfolk, Virginia. This information inspired me to learn more about the significance of the Butler Street YMCA, located in downtown Atlanta, and where its future is headed.

The Butler Street YMCA was started in the basement of the Wheat Street Baptist Church in 1894. The idea was conceived by J.S. Brandon along with his sister in-law, Hattie Askidge, as the organist, both in elected roles. The organization operated in the church until the property on Butler Street was purchased for $10,609 in 1918, after the second elected president, W. J. Trent, started a campaign to raise money for a building in 1909. The new building cost $115,000 and was designed by the architects Hentz, Reid, and Adler in the Georgian Revival and Federal style. The 10,000 square foot structure was constructed by prominent African American builder Alexander. D. Hamilton.

Hamilton was responsible for buildings at Morehouse College and the 1922, post-fire re-construction of Big Bethel AME Church. The YMCA included 48 dormitory rooms, 7 classrooms, a small auditorium, a gymnasium, a swimming pool, shower baths, a café and restrooms. Since the YMCA was constructed in 1920, it remained a staple in Black political, cultural, recreation, and social life. In 1920, Major Robert Russa Moton, principal of Tuskegee Institute, dedicated the Butler Street YMCA. The first president of the YMCA in the new building was Dr. Henry R. Butler (1862-1931), who the street was later named after. His medical practice was located on Auburn Avenue and served as the first Black owned pharmacy in Georgia. Butler’s medical practice lasted 40 years on Auburn Avenue. He served in various leadership positions and created health organizations important to African Americans.

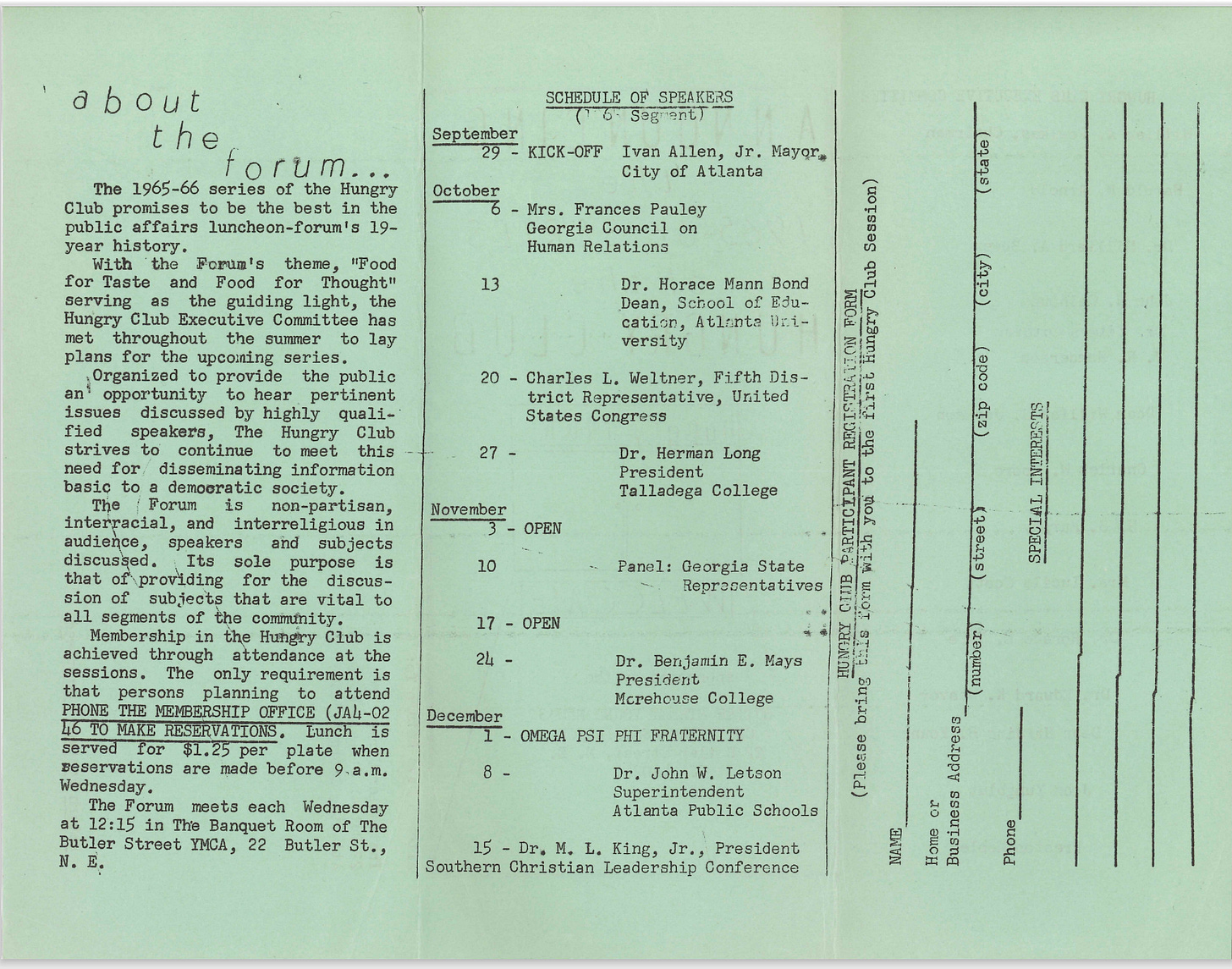

In 1942, A. T. Walden and John Wesley Dobbs started The Hungry Club Forum, which originated as a secret organization and later became more widely known as a liaison between the black community and white elected officials. The club’s motto was: "Food for taste and food for thought for those who hunger for information and association”.

The bipartisan group had prominent speakers such as Civil Rights Movement leaders, politicians, mayors such as the first Black mayor in Atlanta, Maynard Jackson (grandson of John Wesley Dobbs), in addition to local and state politicians, writers, and religious leaders including Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr, and King Sr., Vernon Jackson, and Langston Hughes.9 This organization served as an important space for African Americans to discuss political issues that affected their community and organize their vote into a powerful voting bloc in Atlanta, earning it the moniker, “Black city hall”. Plus, African Americans were able to influence white politicians to vote in their favor by leveraging their collective power through the Hungry Club.

In 1949, lawyer A.T. Walden (Democrat) and John Wesley Dobbs (Republican) created the Atlanta Negro Voters League (ANVL) and regularly meet at the Butler Street YMCA. In 1949, the All Citizens Registration Committee formed to register and amplify the power of African American voters. In 1949, 1953, and 1957 ANVL played a vital role in electing Hartsfield and other moderate white politicians, but 1953 marked a shift. In 1953, ANVL recruited Black candidates for elections. Rufus Clement, president of Atlanta University, which later became Clark Atlanta University, was a league candidate and beat a white incumbent on the Atlanta Board of Education. A Black pharmacist named Miles G. Amos, also won a seat on the city Democratic executive committee due to the support of ANVL and political organizing at the Butler Street YMCA.

As other important Black institutions were forming such as WERD radio located in the Prince Hall Masons Grand Lodge at 334 Auburn Avenue, WERD radio station was the first created and operated by African Americans. John Wesley Dobbs and A.T. Walden, along with Black voters, were able to pressure Atlanta Mayor Hartsfield to hire African American police officers after playing a large role in mobilizing the Black community toward his election. These officers were hired in 1948, and operated out of the Butler Street YMCA instead of the precinct. In a time when Atlanta was dubbed “the city too busy to hate” despite the limited resources for officers, violent attacks, attempted murders, and racially motivated restrictions on the jurisdiction of African American officers. The first Black police officers were sworn in April 3, 1948.

Their names were Henry Hooks, Claude Dixon, Ernest H. Lyons, Robert McKibbens, Willard Strickland, Willie T. Elkins, Johnnie P. Jones, and John Sanders. They were mostly WWII veterans their position after the political activism of the Hungry Club.16 These young men, between the ages of 21 and 32, operated in the basement of the Butler Street YMCA but had many limitations. The men were unable to drive squad cars, work from the local precinct, patrol white neighborhoods, or arrest white people even if they witnessed a white citizen committing a crime. In this Situation they were forced to call for back up. Their main focus in their early policing was to diminish crimes related to bootlegging and public drunkenness, playing on old stereotypes of African Americans as drunkards or debaucherous. With little respect or resources from the city, these eight officers also faced a death threat in which a fellow white officer offered $200 to a member of the public if they could kill one of the Black officers. Other white Atlanta officers leaned into stereotypes about African American men by spreading rumors about witnessing the policemen drinking alcohol while on patrol. Almost half of these officers quit the force after their first year. By 1953, African American police integrated into the local precinct and were able to arrest white citizens by 1963. Some African Americans in the historic Sweet Auburn neighborhood did not trust the officers or see them as a positive force in the community, evidencing a history of negative perceptions and experiences with police in African American communities. Others celebrated the new officers by forming a crowd of 400 the day they were sworn in.

The YMCA served as a hub for the activism necessary to hire these eight black officers and for the larger Civil Rights Movement that led to the eventual integration of the force. The Butler Street YMCA remained a pillar in Atlanta’s African American community well into the 1990s but faced a decline in the early 2010s. Closing operations in 2012, the YMCA’s historic building remains intact today with future plans for development according to Wisconsin based developers, Gorman and Company. The Butler Street YMCA is included in phase two of their development plan for Sweet Auburn titled Sweet Auburn Grande. The plan is to restore the historic building for both community and commercial use in part funded by the $3 Million provided by the Atlanta Boards and Commissions.

Link to the original article: https://dca.georgia.gov/african-american-reflection-articles

References

University of Minnesota Libraries, “African Americans and the YMCA (Archives and Special Collections),” libguides.umn.edu, 2003, Last updated Jun 17, 2024, University of Minnesota, https:// libguides.umn.edu/c.php?g=1088894&p=7940991#:~:text=By%20the% 20mid-1920s%2C%2051%20city%20YMCAs%20and%20an,students%20had% 20been%20established%2C%20with%2028%2C000%20members %20nationwide, (accessed November 12, 2024).

“Butler Street YMCA,” Sweetauburn.us, http://sweetauburn.us/ ymca.htm, Internet Archive, March 6, 2016, http://web.archive.org/ web/20160306035452/http://sweetauburn.us/ymca.htm, (accessed October 9, 2024).

Asanta, Molefi K., and Mark T. Mattson, “The Butler YMCA (Atlanta) Is Founded,” African American Registry, (accessed October 5, 2024). (accessed October 5, 2024).

“Butler Street YMCA,” Sweetauburn.us, http://sweetauburn.us/ ymca.htm, Internet Archive, March 6, 2016, http://web.archive.org/ web/20160306035452/http://sweetauburn.us/ymca.htm, (accessed October 9, 2024).

Asanta, Molefi K., and Mark T. Mattson, “The Butler YMCA (Atlanta) Is Founded,” African American Registry, (accessed October 5, 2024). (accessed October 5, 2024).

The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute, “King, Sr., Speaks at Butler Street YMCA in Atlanta | The Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute.” Archive. kinginstitutte.stanford.edu, April 9, 1936.

Asanta, Molefi K., and Mark T. Mattson, “The Butler YMCA (Atlanta) Is Founded,” African American Registry, (accessed October 5, 2022).

Williams, Louis. "Atlanta Negro Voters League," New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified May 4, 2021, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/ government-politics/atlanta-negro-voters-league-anvl/, (accessed November 11, 2024).

Etling, Laurence. "WERD." New Georgia Encyclopedia, last modified Aug 24, 2020, https://www.georgiaencyclopedia.org/articles/arts-culture/werd/, (accessed November 11, 2024).

“The ‘YMCA’ Cops,” National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, July 12, 2021, https://nleomf.org/the-ymca-cops/, (accessed November 11, 2024).

42 “History of the APD | Atlanta Police Department,” https:// www.atlantapd.org/about-apd/apd-history, (accessed September 25, 2024).

“The ‘YMCA’ Cops.” National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, July 12, 2021, https://nleomf.org/the-ymca-cops/, (accessed November 12, 2024).

Green, Josh, “Sweet Auburn Project Scores 3M,” Urbanize Atlanta, March 22, 2024, (accessed November 12, 2024).

Additional Images